Why We Avoid Hard Things (And How to Start)

Plus, the Overcome Procrastination Protocol, consider it a field manual for doing the hard thing.

The Glaucoma Paradox

Seventy percent of glaucoma patients risk preventable blindness because they do not use their medicated eye drops. These are not people who wish to lose their sight. They are rational adults who understand the consequences. The medication is sitting right there on the bathroom counter. Yet day after day, they fail to take the simple action that would save their vision.

You might argue that using eye drops is not a “hard” task. Physically, it is effortless. But this discrepancy is exactly the point. To the logical mind, a hard task requires sweat or complex thought. To the primitive brain, a “hard” task is anything aversive. Eye drops sting. They blur vision. They serve as a daily, frightening reminder of illness. To the brain’s threat detector, this simple act is high-conflict. It triggers the same avoidance reflex as a difficult tax return. The glaucoma patient is not indifferent. They are caught in a neurological loop that has hijacked their ability to close the gap between intention and action.

The Anatomy of a Hijacking

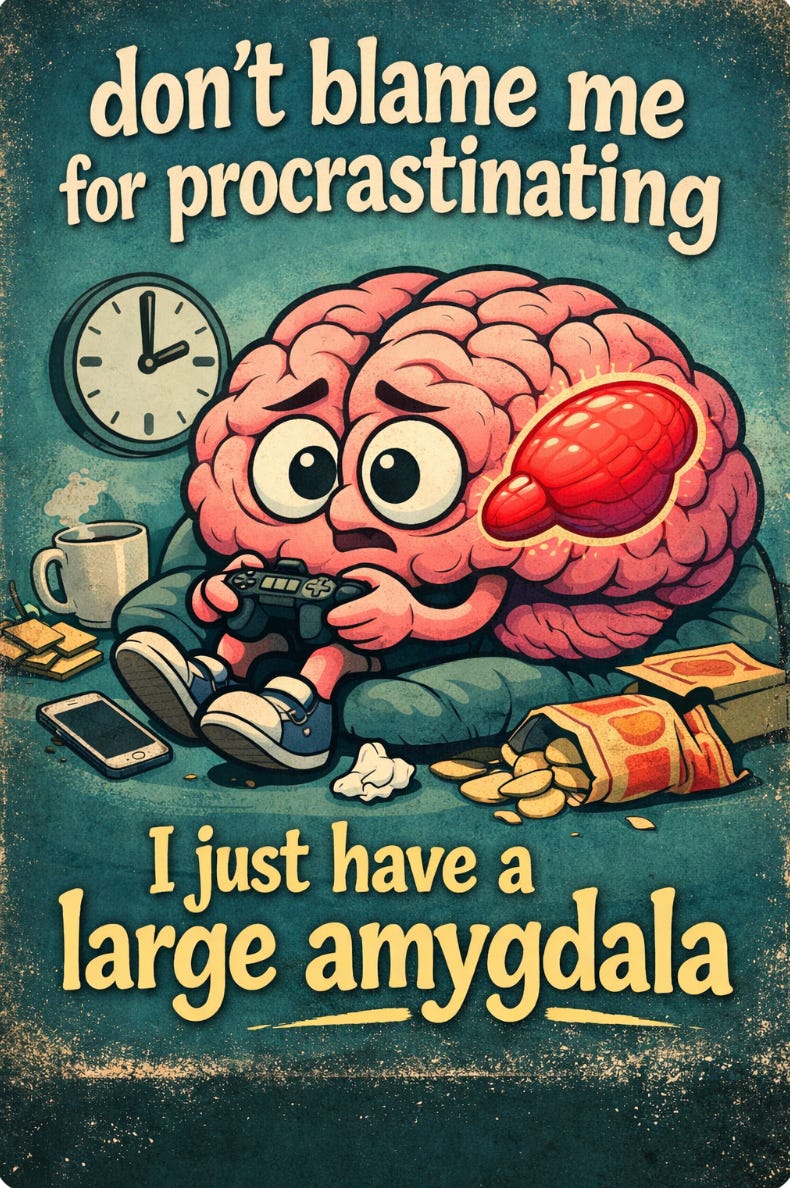

We can now look inside the skull to see exactly what this hijacking looks like. Recent neuroimaging studies compared the brain structures of individuals with varying tendencies to delay. The scans revealed distinct physical differences centered on two specific areas. The first is the amygdala. This is the almond-shaped cluster of neurons responsible for detecting threats and processing emotions like fear. The second is the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. This region acts as the brain’s manager, handling self-control and long-term planning.

The data indicates that chronic procrastinators possess a larger amygdala. Their threat detection center is physically more substantial. Simultaneously, the connection between this alarm system and the brain’s control center is weaker. When a non-procrastinator faces a difficult tax return or a complex essay, their amygdala might flare up with anxiety. Their control center quickly steps in to dampen the signal. They get to work.

The procrastinator faces a different reality. The task triggers a hyperactive alarm response in the enlarged amygdala. The anxiety or boredom feels overwhelming. The weakened connection to the control center means the rational brain cannot calm the emotional storm. The brain seeks immediate safety. It flees the task. This is a biological conflict between a screaming alarm system and a manager who has been locked out of the room.

The Great Mood Repair Hoax

We often try to solve procrastination by buying a new planner. We assume the problem is time management. Psychological research suggests we are looking in the wrong place. Procrastination is less about managing time and more about managing moods. Current theories describe procrastination as an emotion-regulation failure. We delay because the task at hand makes us feel bad. It causes anxiety, boredom, or self-doubt.

We avoid the task to get rid of the bad feeling. This is called “short-term mood repair”.

When you close the spreadsheet to watch a video, you feel a wave of relief. That relief is dangerous. It rewards the brain for avoiding the work. You have taught your brain that the best way to handle task anxiety is to quit.

This dynamic is driven by “hyperbolic discounting”. This is a fancy way of saying we value immediate comfort much more than future rewards. The relief of avoiding the work is happening right now. The pain of failing the class or losing the client is in the future. The brain takes the immediate payout. The tragedy is that this relief is temporary. The stress returns stronger than before as the deadline approaches. The delay was supposed to make you feel better. The data shows it actually leads to higher stress, lower life satisfaction, and worse health outcomes down the road.

The DNA of Delay and the Digital Accelerant

Some of us are fighting a harder battle than others. Twin studies indicate that procrastination is approximately forty-six percent heritable. The genes that influence procrastination overlap almost perfectly with the genes for impulsivity. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense. For thousands of years, humans focused on immediate survival. We grabbed the food in front of us. We ran from immediate danger. Long-term planning is a relatively new requirement for our species.

Biology loads the gun, but our environment pulls the trigger. We live in an “attention economy” designed to exploit our biological weaknesses. Companies engineer apps and platforms to deliver intermittent dopamine hits that our reward circuits cannot resist. The modern environment offers an endless buffet of immediate mood repair. Infinite scrolls and auto-play videos are not just features. They are traps for a brain looking to escape discomfort. The procrastinator is fighting their own biology while navigating an environment weaponized against their focus.

The Myth of the Pressure Player

You have likely heard someone say they work better under pressure. They claim to be an “active procrastinator.” They argue that delaying the task creates a necessary adrenaline rush that fuels their performance. This is a seductive idea. Research suggests it is largely a myth.

Investigations challenging the validity of “active procrastination” find that these individuals still experience the negative consequences of delay. They are not making a strategic choice. They are simply waiting for the terror of the deadline to override the pain of the task. The research indicates that while they might finish the work, they often perform worse and suffer more stress than those who start early. The adrenaline rush is not a performance enhancer. It is a stress response. Relying on panic to induce work is a recipe for burnout, not excellence.

A Multi-Level Protocol for Change

The search for a single cure for procrastination is futile. There is no pill that fixes a behavior rooted in genetics, reinforced by technology, and driven by emotional regulation patterns. However, the evidence shows that significant reduction is possible. We can regain control.

Success requires a multi-level approach. We must address the biological reality by optimizing sleep and managing stress to keep the prefrontal cortex online. We must retrain the mind to tolerate the discomfort of starting a task without fleeing for mood repair. We must redesign our environment to remove the friction of starting work and increase the friction of distractions. We must use social pressure and accountability to make the consequences of delay feel immediate rather than distant.

We are not doomed to be victims of our own amygdalas. Below is the Overcome Procrastination Protocol, consider it a field manual for doing the hard thing.

Please download it, print it, use it, teach it, and share it.

Overcome Procrastination Protocol

A Field Manual for Doing the Hard Thing

You now understand the mechanics. Your brain is not broken; it is simply prioritizing immediate safety (mood repair) over future reward. To bypass this, we cannot rely on willpower. Willpower is a fatigable muscle. Instead, we must build a protocol that accounts for your biology.

This is not a list of tips. It is an operating procedure designed to dampen the amygdala’s alarm and bring the prefrontal cortex back online.

Phase I: Secure the Biological Hardware

Before you attempt the task, you must ensure the machinery is capable of running it.

1. The Sleep Audit The prefrontal cortex, your inner manager, is the first part of the brain to go offline when you are sleep-deprived. If you are sleeping less than seven hours, your manager is asleep at the wheel, leaving the alarm system (amygdala) in charge.

The Rule: If you are chronically tired, do not try to force “deep work” late at night. Prioritize sleep tonight to enable work tomorrow.

2. Acute Stress reduction If you sit down to work and feel that familiar tightness in your chest, your amygdala is already firing. You are in a threat state. You cannot work in this state.

The Reset: Do not “push through.” Pause. Take ten deep, slow breaths. This is not meditation; it is a physiological signal to your vagus nerve that you are safe. You must lower the biological alarm volume before you can engage the logic circuits.

Phase II: The Environmental Architecture

Don’t rely on resisting temptation. Remove it.

3. Friction Engineering We naturally follow the path of least resistance. Currently, your phone offers zero friction for a high dopamine reward. Your hard task offers high friction for a delayed reward. Flip the equation.

Increase Friction for Distractions: Put your phone in another room. Use a website blocker like Freedom or Cold Turkey to lock yourself out of social media. Make the distraction physically annoying to access.

Decrease Friction for Work: “Pre-load” your environment. If you need to write in the morning, open the document and type the first sentence before you go to bed tonight. Lower the activation energy required to start.

Phase III: Cognitive Reprogramming

Hack the software to bypass the “Mood Repair” trap.

4. The “If-Then” Algorithm Vague intentions (”I will study tomorrow”) die easily. Specific algorithms survive. We call these Implementation Intentions. They automate the decision-making process, saving your brain energy.

The Format: “If [Situation X] happens, then I will do [Action Y].”

Example: “If it is 9:00 AM and I have finished my coffee, then I will open the spreadsheet.”

Example: “If I feel the urge to check Instagram, then I will take three deep breaths and stare at the wall for thirty seconds.”

5. The “Five-Minute” Lie The brain fears the magnitude of the task. It imagines hours of suffering. To bypass this, we use a tactical deception known as distress tolerance.

The Deal: Tell yourself you will do the task for only five minutes. Anyone can tolerate five minutes of discomfort. Once you start, the amygdala usually calms down because the actual experience is rarely as scary as the anticipation. This is the “exposure effect.”

Phase IV: Social Engineering

We are social primates. Use that to your advantage.

6. The Accountability Contract Private failure is easy. Public failure is painful. Leverage loss aversion.

The Body Double: Work in the presence of someone else who is working. You don’t need to talk. Just the presence of another human reduces the urge to drift.

The Price of Delay: Make a bet with a friend. If you don’t send the draft by 5:00 PM, you owe them $50 (or you donate to a charity you hate). Make the cost of procrastination immediate and tangible.

Overcome Procrastination Protocol Worksheet

Target Task (Define the specific “Hard Thing” you are avoiding):

1. Biological Check (State Before Strategy)

☐ Sleep Check

Am I rested enough to focus right now?

If no:

Planned nap or earlier bedtime: ______________________________

☐ Stress Check

Do I feel tense, rushed, or mentally threatened?

If yes:

Complete 2 minutes of box breathing before continuing.

2. Environment Setup (Remove Friction, Add Support)

☐ High Friction (Remove Distractions)

My phone or main distractions are located here (out of reach):

☐ Low Friction (Prepare the Workspace)

I have prepared my workspace by doing the following:

(Examples: opening files, clearing desk, closing tabs)

3. Cognitive Script (Decide in Advance)

☐ If–Then Algorithm

“If it is __________________ (time or cue),

then I will ____________________________________________.”

☐ Micro-Commitment

“I commit to working on this task for just ______ minutes.”

4. Social Lock (Make It Costly to Quit)

☐ Accountability Partner

I have told ______________________________ that I will finish this by

______________________________.

☐ Consequence if I Don’t Follow Through

Final Directive: Remember the Glaucoma Paradox. The discomfort you feel is real, but it is a false signal of danger. Your brain is trying to save you from a threat that doesn’t exist. Use this protocol to override the alarm. The goal is not to feel good about the work. The goal is to do the work.

References:

Askew, K., Buckner, J. E., Taing, M. U., Ilie, A., Bauer, J. A., & Coovert, M. D.

Explaining cyberloafing: The role of the theory of planned behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 510–519 (2014). DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.006Beutel ME, Klein EM, Aufenanger S, et al. Procrastination, Distress and Life Satisfaction across the Age Range - A German Representative Community Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148054. Published 2016 Feb 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148054

Chen Z, Liu P, Zhang C, Feng T. Brain Morphological Dynamics of Procrastination: The Crucial Role of the Self-Control, Emotional, and Episodic Prospection Network. Cereb Cortex. 2020;30(5):2834-2853. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhz278

Dong W, Luo J, Huo H, Seger CA, Chen Q. Frontostriatal Functional Connectivity Underlies the Association between Punishment Sensitivity and Procrastination. Brain Sci. 2022;12(9):1163. Published 2022 Aug 30. doi:10.3390/brainsci12091163

Chowdhury, S. F., & Pychyl, T. A. (2018). A critique of the construct validity of active procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.016

Ferrari, J. R., Díaz-Morales, J. F., O'Callaghan, J., Díaz, K., & Argumedo, D. (2007). Frequent behavioral delay tendencies by adults: International prevalence rates of chronic procrastination. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(4), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107302314

Gustavson DE, Miyake A, Hewitt JK, Friedman NP. Genetic relations among procrastination, impulsivity, and goal-management ability: implications for the evolutionary origin of procrastination. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(6):1178-1188. doi:10.1177/0956797614526260

Johansson F, Rozental A, Edlund K, et al. Associations Between Procrastination and Subsequent Health Outcomes Among University Students in Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2249346. Published 2023 Jan 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49346

Kim, K. R., & Seo, E. H. (2015). The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.038

Anierobi, Elizabeth & Etodike, Chukwuemeka & Uzochukwu, Okeke & Ezennaka, Anthony. (2021). Social Media Addiction as Correlates of Academic Procrastination and Achievement among Undergraduates of Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development. 10. 20-33.

Sirois, F. and Pychyl, T. (2013), Procrastination and the Priority of Short-Term Mood Regulation: Consequences for Future Self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7: 115-127. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12011

Schlüter C, Fraenz C, Pinnow M, Friedrich P, Güntürkün O, Genç E. The Structural and Functional Signature of Action Control. Psychol Sci. 2018;29(10):1620-1630. doi:10.1177/0956797618779380

Steel P. The nature of procrastination: a meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(1):65-94. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

Steel, P., & Ferrari, J. (2013). Sex, Education and Procrastination: An Epidemiological Study of Procrastinators’ Characteristics from A Global Sample. European Journal of Personality, 27(1), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1851

Tice, D. M., & Bratslavsky, E. (2000). Giving in to feel good: The place of emotion regulation in the context of general self-control. Psychological Inquiry, 11(3), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1103_03

Van Eerde W, Klingsieck KB. Overcoming Procrastination? A Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Educational Research Review. 2018;25:73-85.

Zhang S, Feng T. Modeling procrastination: Asymmetric decisions to act between the present and the future. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2020;149(2):311-322. doi:10.1037/xge0000643

When your chat notice appeared on my screen, I felt a ping of anxiety. You wrote that you had just posted an article on procrastination and hoped to hear responses from your readers. I am such a hardened procrastinator that my first response was, “I’ll read it later.” (You knew that joke was coming, right? Only, sadly, it’s not a joke.) I have so much respect for your work, admiration for your ability to communicate complex medical workings, and gratitude for how you’ve impacted my life, I felt obligated to read it, as painful as I felt it would be. Well, that’s a paradox, isn’t it? Why would it be painful, I wondered. Why wouldn’t I be eager to gain both insight and a strategy to assuage the cycle of procrastination that has plagued my entire life? This was my first clue. Something in me feels procrastination is necessary to live. It was difficult to begin to read this article. I knew it would dismantle a survival mechanism deeply lodged in my brain. But by now, I trust you have the best interests of your readers in mind. I trust you are dedicated to healing and wholeness beyond a brain’s deeply grooved misperception. As I do with all your articles, I transferred it directly from my inbox to my “Goodreads” app, where I keep all your articles together. But unlike any of your previous articles, I read it immediately, with highlighter in hand. The accompanying animation didn’t play in Goodreads, so I opened Substack to see it, and then read the entire article again. I will study it often. I learned I am genetically predisposed to procrastinate. I learned that, as a trauma survivor, I already have a large amygdala which sets the threat/anxiety/protection/procrastination loop in motion. I learned tools to interrupt its pattern in gentle, sustainable ways. For all this I am very grateful to you, Dr. Laurie!

I am thankful I did not inherit the tendency to procrastinate. If anything, I’ve had to tell myself it's ok to leave the clean laundry in the basket ,not for avoiding putting it away, but to give me space to slow down.

It is difficult to watch others postpone projects. I especially like your suggestion of talking to ourselves. It seems like our mind can hear and understand if we express our concerns. I don’t think we have yet learned to use our breath as a tool for changing our bodies' emotions. Being present and in the moment while slowing breathing is an effective way to speak to my body. Would you consider procrastination a habit that can be changed? Your research is saying even though it feels like it's hard-wired for some people, it can be changed.